From kimmelweck to kimchi

How immigrants and refugees continue to shape Buffalo’s foodscape

Like many former industrial cities in the northern United States, Buffalo’s food roots are deeply entrenched in the soils of other countries. Several of the dishes we now claim as this city’s signatures came here in the minds and hearts of first the Germans, who left revolution and famine to settle on the east side starting in the 1820s. They’re credited with introducing sliced roast beef on kimmelweck rolls, steins of lager, and the juicy bratwurst that grace tailgate grills at Ralph Wilson Stadium on football Sundays.

Pickled herring at Euro Deli on Union Road. Germans – my mother and grandmother included – eat this stuff as a traditional good luck gesture at New Years.

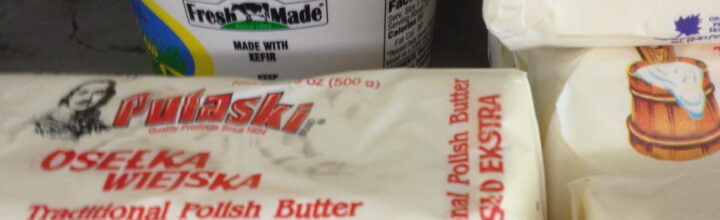

More flavors arrived with the Irish, who fled the Great Potato Famine in the 1840s and filled South Buffalo with the classic Friday fish fry, hearty stews, and corned beef and cabbage. Next came the Polish, who left their constantly dividing country in the 1870s and brought fragrant kielbasa, comforting goulash, and pierogi to Buffalo’s east side. Italian immigrants left their homeland’s economic turmoil around the turn of the century and settled in the city’s northern sections, where generous portions of pasta and sauce, rich pastries, and spicy stuffed peppers are still served.

These European families came in such numbers that as of the 2000 census, Buffalo residents still reported the largest ancestral ties to these four early immigrant groups: German (13.6%), Irish (12.2%), Italian (11.7%), and Polish (11.7%).

Fast-forward more than 100 years and the Queen City’s influx of faces and flavors is quite different. In 2012, the International Institute of Buffalo resettled refugees from Burma, Bhutan, Somalia, Eritrea, Sudan, Iraq, and Iran. Over the past century, countries of origin have shifted as war and political upheaval shape realities around the world. When Denise Phillips Beehag, the Institute’s director of refugee and employment services, first started working with refugees 14 years ago, she helped people mostly from Kosovo, Bosnia, and Vietnam. And before them came immigrants and refugees from Puerto Rico, China, Cuba, Mexico, The Philippines, India, Jamaica, Haiti, Korea, and the former USSR.

With these new Americans comes a treasure trove of traditional ingredients that are fairly quickly weaving themselves into the fabric of the Buffalo food scene. Businesses that cater to this huge spectrum of international tastes are opening at a greater rate than ever before; a drive down Buffalo’s main thoroughfares, especially Hertel Avenue, Niagara Street, and Grant Street, reveals a veritable “It’s A Small World” ride of ethnic grocers and eateries. Beehag says the IIB is constantly updating its Map for Adventurous Eaters, which provides locations, descriptions, and contact info for dozens of global restaurants and food stores around the city. The map is fundraiser for the IIB and is available for a suggested $10 at the IIB office located at 864 Delaware Avenue.

I don’t know what kind of mushrooms these are or what’s up with the small children on the packaging, but they were gorgeous and delicious in a stir-fry.

There are so many, it seems, that while driving down Grant Street, it’s easy to wonder how several Asian markets can survive in such close proximity to one another. The answer? West side Chinese families living near Golden Burma market today have similar shopping habits as the Polish families who lived down the block from the Broadway Market long before cars clogged city streets.

“Many people shop the old fashioned way – every day,” explains Beehag. “The stores need to be close to home for people without reliable transportation – within walking distance – so there’s plenty of room and opportunity for new businesses to open in each neighborhood.”

Even the bigger grocery stores are stocking shelves to match grocery lists of Buffalo’s modern immigrant families. The Tops on Niagara Street, for instance, caters to its largely Hispanic neighborhood, filling nearly a third of its produce section with Latin staples like fiery peppers, aloe leaves, avocados, papaya, and root vegetables like apio, malanga, name, yautia, and yuca.

It’s about more than grocery shopping, though. Ethnic cafes and shops not only breathe new life into forgotten pockets of the city, they act as impromptu community spaces where ties to home are shared and strengthened.

“Food is such an important part of everyone’s culture,” says Beehag. “It’s especially true for our current refugees. Many come here and leave everything behind. So when they can taste or smell something that they associate with home, it means a lot. Food is sometimes the only piece of home they can bring with them and pass down to their children.”

This is true for Soe Maung (Soe for short), who owns Kyel Sein Hein, the Burmese food stand inside the West Side Bazaar on Grant Street. Since serving his first customers in March 2013 with cooking skills and recipes he learned from his mother, Soe says the Bazaar has played an important role in Buffalo’s Burmese community.

“It’s a meeting place for Burmese families and friends,” says Soe. “They come to have tea, hang out, and talk about what’s going on in Burma and with people we know.”

Soe is quick to point out that it’s not only Burmese people who fill the café tables at the West Side Bazaar, though. Americans, immigrants, and refugees alike come for the unique experience of being able to taste foods from six different cultural kitchens that share roughly 500 square feet of space. In addition to Burmese food, there’s Thai, Ethiopian, Peruvian, Japanese, and Loatian menus to choose from. In true Buffalo style, Frank Zarcone and Sons Italian meat market is right next door.

The variety of pickled things available at many cultural stores is fascinating. While many labels are not printed in English, with simply prepared, traditional foods it’s easy to just look and see what produce and spices are included.

Up the street, Vineeta International Foods offers the grocery equivalent of the Bazaar’s international tour; the cavernous store carries staples for the West Side’s growing Asian, African, and Middle Eastern populations. Its produce section is overflowing with tropical fruits and vegetables including tamarind pods, tiny peppers and eggplants, prickly jackfruit and durian, bitter gourds that resemble spiny cucumbers, mysterious mushrooms, fuzzy coconuts, fragrant stalks of lemongrass, and endless bags of herbs and leaves. Shelves are lined with hundreds of spices, exotic juices, dried beans, noodles, sauces, and jars of everything under the sun. Fresh and frozen meat and seafood selections include nose-to-tail cuts of everything from goat to eel.

Should all of these unfamiliar foodstuffs be daunting to cooks whose recipe boxes are brimming with mom’s meat-and-potatoes traditions? Sami Amin, general manager of Jerusalem Halal Market and the adjoining Manakeesh & More Middle Eastern Café and Bakery at 1150 Hertel Avenue, doesn’t think so. The store’s shelves and freezers are full of treasures including halal meats, grillable halumi cheese, olives of every size and color, pistachio candies, honeycomb, dried dates and figs, tahini, and frozen phyllo dough – and plenty of advice to go with them.

“People ask me all the time, ‘What’s this, what do you use it for?’” Amin says. “They want to learn about the different foods, and I like to explain what everything is. There’s no reason to be shy.”

Many of Buffalo’s newer cuisines, especially those that hail from warmer climates, feature vegetables and fish more prominently than the heavier foods common in colder European motherlands. Absent are heavy flour-based items, rich meats and cheeses, and fried foods; instead, dishes are resplendent with lively chilies, bright herbal flavors of lemongrass and cilantro, translucent rice noodles, and a rainbow of fresh fruits and vegetables. People who don’t consume meat, gluten, or dairy can find oodles of options on ethnic menus that go way beyond what’s available at restaurants featuring continental cuisine.

If you look closely, though, the similarities between Buffalo’s old world European roots and its global future may outweigh the differences. Lovers of Italian sweets might enjoy the Cuban quesitos, a crisp pastry tube filled with sweetened cream cheese, or the pastellilos de guayaba, a sandwich cookie featuring two flaky squares pressed together with guava paste and dusted with powdered sugar. Every culture has its own version of meat-filled dough – Italian ravioli, English pork pies, Latin empanadas, multi-cultural samosas, Chinese dumplings, Greek kreatopita. Eastern European sauerkraut finds a fermented cabbage cousin in Korean kimchi. The stinky German limburger cheese has moved over and made room for the equally stinky Vietnamese Bun Mam fermented fish soup. Everyone sips tea, takes pride in their best creations, and celebrates holidays with the recipes they grew up with.

This has always been the City of Good Neighbors; the block party potlucks have just become more diverse.

__________

Here’s just a tiny sampling of some of the international treats available at Buffalo’s newest shops and eateries:

Kyel Sein Hein Burmese Restaurant

Inside the West Side Bazaar, 25 Grant Street

- Coconut chicken soup generously laden with hunks of chicken thigh, long egg noodles, chopped hard-boiled egg, and rich coconut broth served with a small pile of thinly sliced red onion on the side. At $5 for a huge bowl, it’s a soothing steal.

Pure Peru

Inside the West Side Bazaar, 25 Grant Street

- Chicha morada, a chilled drink made with purple corn that has been boiled with pineapple, clove, and cinnamon, then sweetened with sugar and lime juice; it’s reminiscent of the color and flavor found in hibiscus iced tea

- Banana leaf-wrapped tamales stuffed with a mild blend of cornmeal, peanuts, onion, hard-boiled egg, peas, peppers, and either roast pork or hunks of beef

Golden Burma

92 Grant Street

- Preserved green baby mango halves from Thailand, vacuum packaged with a vial of chili salt for sprinkling; tart, sweet, spicy, salty all at once

- Pantry staples for things like stir-fry and spring rolls – cans of thin baby corn and water chestnuts, sheer rice noodles, dried mushrooms, and good-quality fish sauce

Vineeta International Foods

Grant Street

- Soan Papdi, an Indian coconut and wheat flour candy. Its texture is like a finer version of a crispy Butterfinger center; sweet, melt-in-your-mouth coconut studded with pistachio. It comes in a small rectangular plastic tub with a snap-on lid and a little plastic spade to break pieces off.

- Everything else. Seriously. Get a cart – lentils, fresh coconut, curries, soft naaan, dried mushrooms and chilies, lychees nuts in syrup, and no shortage of Sriracha and other spicy accouterments

La Kueva Puerto Rican Restaurant

1260 Hertel Avenue

- The appetizer/side portion of the menu features several choices that satisfy a craving for fried comfort food, all for under $4 each. Especially good are the chicken pastelillos (a half-circle pastry stuffed with shredded chicken, cheese, red pepper, and potato), the sweet fried cornbread stick filled with gooey cheese, and the mofongo, fried green plantain mashed with garlic, oil, and drizzled with more garlic oil. Try their house-fermented chili sauce, which lives in a clear glass bottle on the counter.

Jerusalem Halal Market

1146 Hertel Avenue

- Halva, a Mediterranean tahini (sesame) fudge with pistachios. Light, nutty, and not too sweet

- A shelf of olives that would rival any grocery olive bar in selection, quality, and price; a 28-ounce package of small, firm green olives from Turkey costs just $5.

2 Comments

mom

April 14, 2014your superb writing makes the food come alive – even if it’s cooked and hopefully……dead. Now I want to try it all!

Rebecca

April 17, 2014I love your blog! Educational, entertaining … And always mouth watering!!